Waiting for Spring to Really Bloom

Eggs are actually a seasonal spring food, so appreciate them extra hard this spring!

Spring has always been the hardest season for me. At springtime at our farm, and the farms we worked at, I always become both excited and anxious to harvest some greens from the ground, and so eager after a long winter for a fresh salad, that my mouth just waters looking at the stubby, muddy soil.

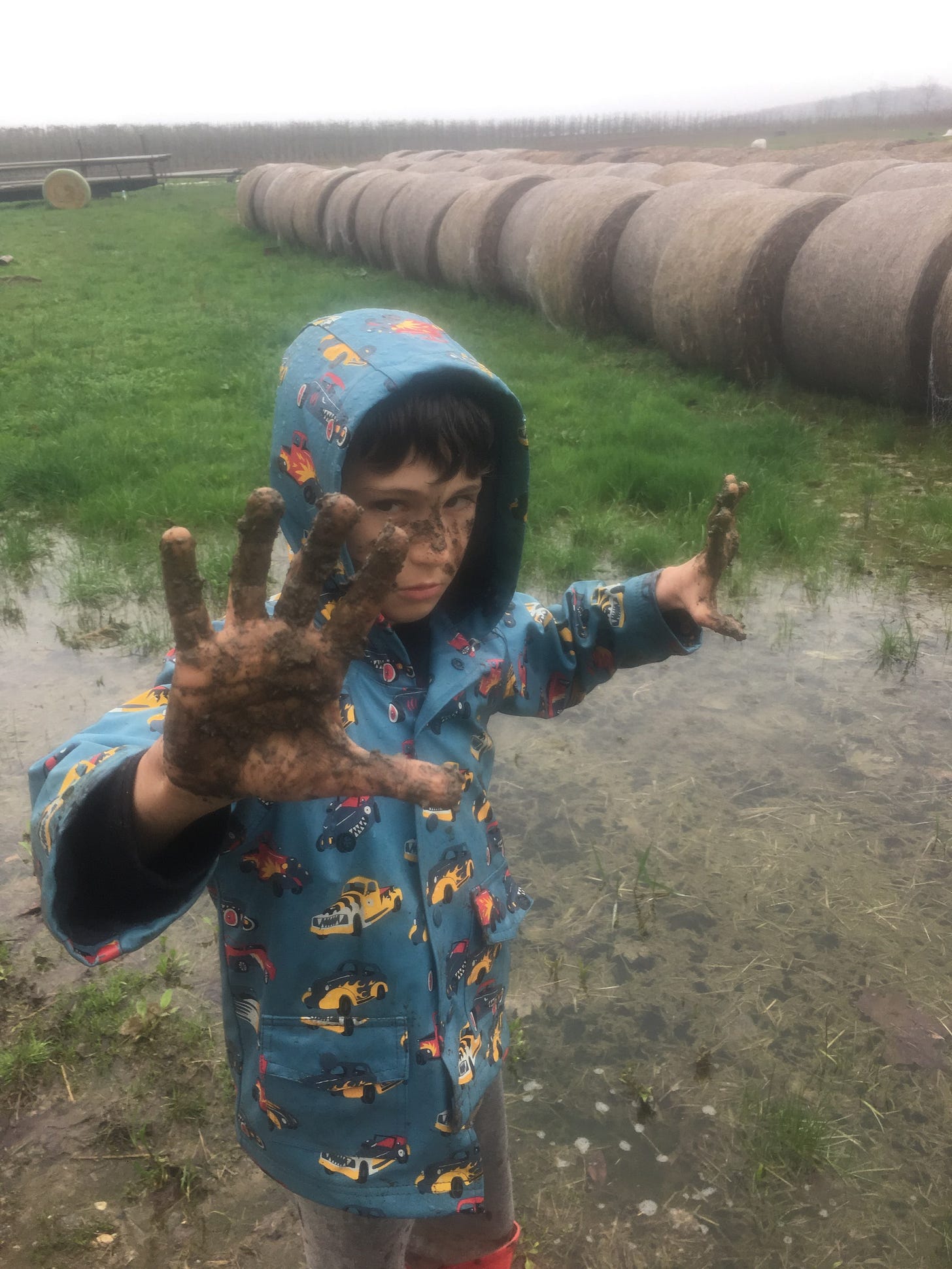

This has been a harder-than-usual April for me. Though this will all change starting in a couple of weeks (details to come—sorry for being secretive, but we weren’t sure exactly how things would shake out or what we were going to decide to do this season until recently!), we have been pinballing back and forth from our friends’ farms in Illinois (shout out to Rob and Christina and Mike and Clare!) to deal with our equipment, and to my parents’ house. This has been the first April in over fifteen years where we were not in a greenhouse seeding plants, and also not harvesting from hoophouses. We are not getting new chicks or planning out fields. We are not in the soil yet, except for the small garden I started planting for my mom in her backyard, but we will be somewhere soon, and until then, I am trying to be more comfortable in the limbo.

For the last two Aprils, we had been in our RV bus, parked at a farm in New York. We dyed brown eggs with dye made from beets and blueberries for Easter, and hid them around a creek. We were harvesting salad mixes and other crops from the hoophouses. We even raised chicks in a cardboard box for this farm, heritage ones that lay green and blue eggs. (As if our tiny space wasn’t small enough, we then had a red light glowing and the constant chirping of squeaky chicks as our constant background and soundtrack.)

Eggs are actually seasonal—their laying is triggered by the increase in sunlight, and are therefore traditionally a springtime food. Farmers can artificially add lights to their coops in the winter in order to not disrupt egg production—otherwise, chickens will lay very few eggs or just take a break all together during the darker months before spring comes again.

When it does get warm enough, chickens who lay eggs—called “layers”—are commonly raised outside by organic farmers. We have always made sure to raise our chickens outside, but we’ve always been well aware of its risks. At our farm in Illinois, we had many predators that impacted our flock.

Coyotes were one of our most common ones. Hearing the coyotes howl was one of my favorite parts of living at our farm. Despite the rampant suburbia that had paved over meadows and forest with its roads and development, wild things still unstoppably emerged, like dandelion flowers pushing their way through cracks in sidewalks or coyotes making dens in small shrubby corners next to parking lots and bike trails. The mythology of coyotes run as deep as earthworm burrows. In Bryce Canyon in Utah, there are stories of the “legend people”, who were there long before European invaders or even before the Native People. The legend people were said to be greedy people who used and took everything in their environment (much like today’s humans), and as their punishment, were turned into hoodoos, giant pink rock formations, by Coyote, who was said to be a trickster god. At our farm, coyotes were usually seen as a problem (though this was unfair to the coyote, since they are important at keeping rodent populations down, which is very helpful to the farmer), but also were a fascination to us—in the early spring days, I would sometimes see them, in the daytime, wandering around the woods or our backyard, looking scraggly and haggard and hungry after a long winter. “Poor coyote,” I’d always think, admiring their survival.

Most nights back then, I’d take turns putting chickens up at night with Alex, which was often times our least favorite activity of the night; when you are dead-tired from farming/child-rearing/business keeping, the last thing one wants to do is, after dinner, in pajamas, go out after the sun goes down and walk a quarter mile to close up a bunch of chickens. It isn’t hard, as long as you go after it gets almost completely dark; if the sun is merely setting, there will be several squawking birds outside still, basking in the last wisps of light. If it is completely dark, though, the chickens will all be squawking their goodnights to each other inside, cuddled up and ready to go to sleep.

If the sun went down long ago, however, and you have not yet closed them up, there is the danger of a night time Coyote, sneaking in like a bandit, grabbing a few, while traumatizing the others in the process.

One night, after a particularly harrowing day of broken down tractors and goats getting out of their fence, Alex came in for dinner covered in black smears of diesel from trying to fix said tractor problems. I was trying to get the boys to bed at a decent hour, reading them a book, when I looked at Alex’s face in the other room, slowing falling asleep on the couch. I put the book down gently on the boys’ bed and told them I’d be right back.

I put on my boots, stuffing my pajama pants inside, and trekked out to the field. We rotated our chickens using a solar-powered electric fence and a chicken coop on wheels, built with wood and scraps on top of an old manure wagon by our good friend Kevin, along with Alex. Depending on the weather, we wheeled around the chickens every few days, and we closed them in using a latched door every evening when the sun went down to protect them from night predators. As I walked out, with the sounds of katydids and cars whooshing, I began hearing something else as I neared the field. Instead of the usual low murmuring of chickens bidding themselves goodnight as they waddled into their home, I heard what I did not want to hear in the dark: terrified squawking.

I began to then run. They were scared, and most likely, it was because a coyote, or possibly a fox, was inside the fence. I rushed over, not seeing anything yet but the darkened images of chickens out of the coop instead of in. I started shrieking, clapping my hands, and as I ran closer I saw an inky silhouette of a coyote, leaping like an elegant dancer from the inside of the electric fence to outside of it, a poor moonlit fluffball of a chicken in its mouth. It then darted away into shadows.

I wondered how many others were injured; hopefully not many, I thought. Most of the hens were inside the coop already, but there were four dead ones that lay on the ground, looking like deflated balloons of feathers and blood. A few worried stragglers were still milling around, squawking and making shaky footprints in the mud. Feeling both impatient and sad I had not gotten out there faster to close them up, I started lifting them up and putting them into the coop myself. I was not a big chicken nurturer, or, at least, not the same way I had been with the goats. We only had four goats, as our landlords did not want us to have any more than that, and they all had names. Chickens, however, were a different story. Each season we had anywhere from 400 to 500. I liked that we raised them the way we did, putting a lot of energy into their pasturing, but I was also perpetually annoyed with them. They took a lot of the farm’s time, and although I felt very strongly about animal rotation on a farm, I wasn’t really sure we were even making a profit at this point from the eggs. But tonight I felt bad from them. In my mind they looked wide-eyed, and their red feathers looked panicked and ruffled, like cartoons that had been struck by lightning. “Bawk?” They seemed to softly ask me. “Yes,” I whispered back. “He’s gone.”

Raising animals outside was very important to us, but it is no wonder why farmers choose to not do so. Predators are all around, from four-legged ones to airborne ones, like red-tailed hawks or owls. By our third season on the farm, I had seen so many red-tailed hawks squeezing chickens in their talons on the ground, that we figured we would lose, on average, twenty-five birds per season.

That said, the benefits for us outweighed the hardships. Raising an animal in the outdoors on fresh pasture really makes them healthier, and in turn, makes the food (either eggs or meat) healthier. A pasture-raised egg will have a brightly colored and nutrient-dense yolk, high in vitamins and Omega-3s. We also felt it very important to raise them on organic supplemental feed (all chickens need to have some grains and minerals to be truly balanced). Years before, we had started feeding them just an “all-natural” feed, but when I read an article one winter on glyphosate build-up in non-organically fed birds, we became very strict about filling their bodies with chlorophyll’s liquid sunshine, bugs, and chemical-free organic grain. On top of that, during our last year at the farm, I realized also how much carbon we could sequester in the ground with our plants and animals, and started a more strict animal rotation system with our goats and chickens to focus more on that.

Everything we have learned, I know, will help us at our next location. Right now, though, I feel like a dormant seed, waiting to wake up, wanting to burst forth my cotyledons and get started. In my mom’s backyard, I found lily-of-the-valley, a spring ephemeral, and stinging nettles, an exciting sign of spring, especially for an herbalist. Like a coyote, there is plenty of folklore behind these plants. Lily-of-the-valley is said to be a protector of a garden, along with being a fairy plant (fairies are said to use their tiny white flowers as tea cups). I harvested some of the nourishing nettles to eat, and left the lily of the valley to protect the emerging garden. I’m now trying to talk my mom into adding a few chickens to their yard for both eggs and garden fertility—why not imagine big? The garden I’m making in my parents’ yard is small so far, but it has room to expand. And just like spring, it is full of possibilities.

In the Tiny Kitchen:

I have been using my parents’ kitchen, and also dreaming of our own kitchen that we will move into soon. And the kitchen will not be an RV bus kitchen! Alex and I basically made a promise that no matter what, we were not going to be in the bus this summer, and ideally, hopefully, be in an actual home of our own. So we are going to make good on that promise! I have been making more recipe development plans. I am missing our old hoophouses and our perennials that we had at our old farm, and missing being on any farm at all right now, but I am trying to funnel that restlessness into kitchen production instead. It is working ok so far.

On the Road:

We are still in Illinois, but leave tomorrow (just in a car) to go to visit Alex’s family in Virginia. Then we come back, and start the move. We are working out the exact plans, and will know more soon!

We are so excited to know your plans! Can't wait! :-)

Good luck to you on your next adventure/venture.